How the Illusion of Landownership, Misplaced Potentiality, and a Debt-Based Paradigm Created the Global Housing Crisis

One of the most talked about social issues in Canada (and in other nations) right now is the country’s housing crisis. Not only has the cost of owning a home skyrocketed, rental prices, in parallel, have also escalated to reflect the pressures of this housing market. Additionally, rising inflation rates have affected food costs and household expenditures. Literally and figuratively, the cost of “living” has reached a pinnacle point. Economists, politicians, planners, and social activists have much to say about this topic, but from the perspective of an eco-philosopher (aka me) who sees “eco” as the tie between our physical and spiritual homes, this housing crisis perfectly illustrates the relevant mirroring between our economy, our ecology, and the ecopsychology of our human psyche.

The housing crisis is something that I’ve become quite interested in lately for two reasons: 1) my interest in the eco-spiritual aspect of the notion of home, and 2) how it mirrored my own experience in the last year with the housing market, including selling my 1-bedroom condo unit and finding a place to rent. Since I am not an economist, I come to this topic from a way that builds off of my intuitive knowing and exploratory thinking. Most fundamentally, I start with a perspective that sees “home” as something beyond anything a monetary number can represent.

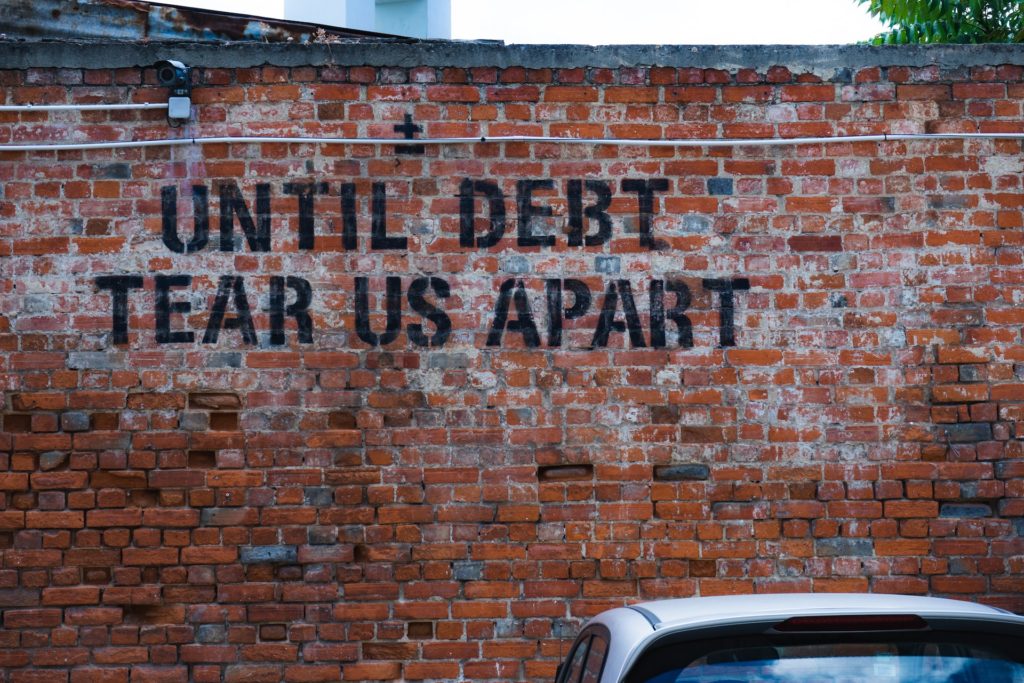

The economic context of human society: a debt-based paradigm

According to the Canadian Real Estate Association, via The National Post, the average cost of a home in Canada in February 2022 was $816,720, which was more than nine times the average household salary. In major cities such as Toronto and Vancouver, the affordability ratio is even more unhealthy. For example, housing in the province of Ontario (which includes the City of Toronto) costs 22.5 times the average disposable income (Source: BlogTo). Even with the “cooling” effect of the 2022 interest rate hikes, the average house price in Toronto in December was still over $1 million (Source: Zolo Realty), while the average monthly rent for a 1-bedroom had risen 23.7% over the span of the year to $2,551 (Source: Rentals.ca).

The most common narrative to explain the predicament we are in right now is that there is a shortage of housing supply. But before I start looking at whether housing shortage is really the crux of the issue, I cannot ignore the foundational paradigms of our global economy, more precisely, how our human relationship with money and debt has created a heartless and unsustainable economic system. Note that the etymology of “economy” literally means household management, but the irony of our global economic system starts with the fact that the most powerful countries in the world are in excessive debt (e.g., United States $24 trillion, UK $8.73 trillion, China $2.64 trillion in June 2022, according to Wikipedia).

As someone who has not studied economics, I always wondered, who are these countries indebted to? And if we are functioning fine, at least on a superficial level, does this debt even matter? Turns out, from my internet research, that these countries are in debt to many sources: citizens, foreign banks, central banks, and even from different divisions of the nation themselves. But if all the debt is hypothetically returned and cleared, who has the excess money? The answer: nobody. The debt is a manufactured illusion made real.

Central banks create money by having the ability to lend multiple times more than their reserves, charge interest, and consequently, affect inflation (Source: Investopedia). Despite not having a PhD in economics (although I have one in environmental studies, which is perhaps a parallel to the “management of home”), I can conclude that a problem with our economic and political systems is that we operate from a purposefully designed co-dependent and debt-based paradigm.

Money as potentiality or limitation

If we go back to the essence of money, we understand that it has no value. Money is only a transactional “middle-person” used for the exchange of things with value. But in a debt-based system, money has what I call “potential value”. When we have money, we have the “potential” to exchange it for something else. Or alternatively, we can lend it to create more potential. But potential is still a relative phenomenon. Capitalism says that markets are about supply and demand, which is true at a practical level, but supply and demand are still based on where we place value as a collective society. Therefore, the potentials of our money are dependent on how much we value or devalue something both personally and collectively.

So, depending on which side of the transaction you find yourself, your relationship to money can be seen in terms of potential value or limiting debt. While potential and limitations seem like opposites, in a debt-based economic society, this relationship is muddled up. We can use debt, that is, the ability to borrow money, to create more potential for ourselves (e.g., to buy a house on a mortgage). We can also use other people’s debt, that is, their limitations, to create more potential for ourselves (e.g., create money through interest loans to others). We can use the potential available through money to help others achieve more of their own potentials or continue to exploit other people’s limitations for the growth of our own potential. But if we choose the latter, our world inevitably becomes unsustainable. Whether we know it or not, we would be heading towards dystopia.

A misplaced value system: we aren’t worthy of living

When the cost of living and housing keeps increasing while wages remain stagnant, it means that collectively as a society, we have decided that there is little value in our human labour and liveability. The paradigm that we’ve subscribed to is that the standard of basic living is merely a luxury experience for those who manage to maintain or play the game of the debt-based system.

Now back to the government and CMHC’s rationale (via CBC News) for the housing crisis: housing shortage. Intuitively and logically, I don’t buy into this idea. If we take away the price tags and compare the number of available homes on the market to the number of people needing homes, if those numbers are equivalent or sufficient for the number of people, then, simply, we do not have a housing shortage. As research reveals, according to SFU City Program Director Andy Yan and BMO’s Capital Markets report, the housing to population ratio has been consistent in British Columbia and housing development even surpasses population growth in Ontario (Source: Better Dwelling).

From a lived experience perspective, if you’ve been searching for a home to rent or buy in Canada like I have, you would know that the issues are cost and competition. Yes, there is a “shortage” of “affordable” homes under the paradigm of supply and demand economics. Yes, it’s hard to secure a home. But the reason is not because there aren’t enough homes available, but rather, it is because we’ve created a false sense of scarcity. The value we place on ourselves and what we can do in this world in exchange for potentiality (i.e., money) is not meeting the requirements we’ve placed on our own security and comfort. To put it simply, the collective message we’ve subscribed to is that we (humans) aren’t worthy of living.1 Alternatively, for some people, the message may be that I am worthy of living, but others are not.

The root cause: the illusion of landownership

Ever since I heard systems theorist Fritjof Capra call our modern predicament the “crisis of perception” (The Turning Point 1982, Mindwalk 1990), I’ve been referring to our current social-ecological crossroads as the “crisis of not-belonging”, leading to our “collective homelessness.” These phrases encompass the reality of our global housing crisis, but they go much deeper…to the home we make on Earth with the rest of nature and the homes we find within ourselves.

In Canada, Truth and Reconciliation affecting Indigenous-Settler relations is a crucial political agenda. Politicians may categorize Indigenous relations and the housing crisis as separate social issues while citizens may categorize them under the umbrella term of social justice, but from an eco-spiritual perspective, they come from the same core problem, that is, that landownership is an illusion. The land is its own entity. Other forms of nature, beyond humans, also have their own agency. As human beings, we don’t own the land and never will. We can only be stewards of the land.

The honest review is that, at the collective level, we’ve done a bad job at being stewards. The biggest mistake is that humans have confused stewardship with ownership. This illusion is a fundamental part of our debt-based society. Civilization and modern economics have created potentiality, in the form of monetary value, out of something that does not exist (or at least in the way they were originally intended). Systems tend to backfire when we manifest the illusion of scarcity. For example, when the bank prints money, we get inflation, and inflation leads to a recession. That is a slap on our faces telling us that we’ve deluded ourselves, and yet not many people realize this.

A choice point: where are you going to invest in your potential?

Then, can the pursuit of money be sustainable? That depends. Potentiality in the form of money is not always a bad thing depending on the motivation and the intention. The transaction of value for potential can create something better in the world or it can be used to feed cycles of fear, shame, and unworthiness. This distinction can be hard for many people to discern because in a capitalist society, we spend a lot of money on escapism. And usually, escapism is about fear, shame, and unworthiness.

Historical social conditioning has created distortions in our human relationship with money. Many people with good intentions have limiting beliefs (i.e., psychological barriers) about receiving money and becoming rich. Stories that describe altruism as the act of charity and giving your money or possessions away, or that the rich and powerful will exploit the poor, float in our conscious or subconscious memories. Sometimes we forget that we need to be abundant in the first place, not necessarily of money but abundant nonetheless, to have something to give to others.

New Age teachings based on the principles of quantum physics constantly remind people that everything is energy: money, the stuff we buy, the land we live on, our bodies, and even our thoughts and emotions. The First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy cannot be created or destroyed. Accordingly, the energy we’ve borrowed to create illusions (of scarcity and misaligned potential from nature) must come from somewhere.

What are we indebted to by choosing to live the paradigm of a debt-based society? My guess is our (or a fellow human being’s) self worth, self love, self dignity, authenticity, courage, dreams, compassion, friendliness, etc. We’ve either willingly lent these parts of ourselves out to feed a dysfunctional system with false hopes for a better return, or we got them stolen unknowingly. But we owe it to ourselves to return this loan on our worth—only then can we find our true homes.

In a few months, I will again be looking for a new home in the rental market. Through the debt-based paradigm, the prospect of finding my outer refuge is dim, even more challenging than last year because of inflation. But I know that the investment in the faith of my own worthiness, and the potentiality available in the depths of my inner oasis, are what it will take to break out of the illusions.

- We could argue that the message is about “living well” because, technically, living on the streets is still “living”…but the healthcare crisis in Canada and in other countries could be a telltale that our predicament goes to the core of our worthiness to live in general. ↩︎