Ways of Seeing the World: The Relationship Between Subject and Object

While famous philosophers such as Husserl, Heidegger, or Merleau-Ponty took different phenomenological approaches to understanding and structuring methods of studying human experience, phenomenology as an everyday concept can still feel very abstract. This ambiguity is especially true when phenomenology is used to discuss something as abstract as “place”. One way to organize the ways we experience is to consider the relationship of subject and object.

An older version of this post was originally published in an old blog from 2017.

Between subject and object

Approaches to phenomenology vary across scales. That is, the use of phenomenology can range from studying the nitty-gritty material details of day-to-day living to asking big questions about our existence and relationship with the cosmos. Phenomenology is relevant to anything we want because it is a way to understand both the details and the essences of being in the world.

One way to organize how we can understand experience is to consider the relationship between subject and object. But as my first PhD supervisor had warned me, talking about subject and object as two separate things can become problematic. By separating things as subject and object, we may be perpetuating a dualistic and binary perspective of the world. But, in my opinion, unless you already have a good grasp for seeing the world from a non-dualist perspective, considering subject and object as a relationship can be helpful to move us beyond unhelpful dualisms.

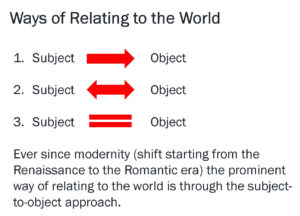

Put simply, we perceive the world from one of these three perspectives at any given time:

- A one directional relationship from subject to object. (Example: I use my desk.)

- A bi-directional relationship between subject and object. (Example: I use my desk. My desk supports me and my work.)

- A diffusion of subject and object. (Example: My desk and I are a phenomenological unit in relation to the work I create.)

Objectivity and research conventions

Despite Husserl’s very methodical way of “bracketing” out pre-conceived biases, judgements, and assumptions in studying experience, phenomenologists, for the most part, reject the idea of subjects and objects. Seeing the world through a subject to object lens is considered dualistic, over-rational, and anthropocentric.

However, a subject to object approach to seeing the world is most conventional in our modern world. Objectivity has a history and is largely a by-product of René Descartes’ mind-body dualism. The scientific method strengthens this approach. However, in research, the terms are inverted. The researcher is assumed to be separate from and objective to the research subject.

Ways of seeing landscapes

So when we consider something as experiential as being in a place or a landscape, can we consider the subject-object relationship in the same way?

Well, for starters, as a person trained in landscape architecture, I know that designers and engineers will inevitably look at landscapes through a subject to object lens. For example, site analysis, site inventory, and the use of maps are all ways to objectively look at landscapes to record data. And even if the study goes deeper, such as studying a landscape in terms of its sociopolitical context, its pictorial quality, or the patterns that exists in it, the subject to object perspective is still in place.

The next level of consideration is to consider reciprocity and the agency of non-human entities. When we look at landscapes as the instigator of sensory and emotional effects, landscape matter become part of a balanced relationship with the perceiving subject (i.e., me or you). In better landscape designs, the reciprocal relationship between subject and object is considered. In these landscapes, the landscape has a language of its own, creating a “dialogue” between itself and the designer or the user.

Finally, when the whole of landscape, rather than just its material and immaterial components, gains authority and voice, the subject and object distinction is blurred. When we can see landscape as something archetypical or enmeshed in existential order, the objectification process disintegrates. In the best landscape designs, the landscape is no longer an object because it can speak for itself. The landscape will bring awareness to its user, as a being who perceives the world and also exists in it.

Unfortunately, landscapes are much devalued in our capitalistic society. Often times, the effort to dwell, even just objectivity, at a landscape is often foresaken due to external pressures such as political, financial or personal constraints. A subject-to-object approach is, therefore, usually the first step to taking landscapes seriously.

Opening up our field of perception

The reason why we often neglect enriching aspects of our existence (e.g., landscapes, philosophy, emotions, experiential awareness, etc.) over what we is deemed more practical and realistic is because social conventions can make us biased towards certain ways of perceiving. These biases can affect the way places are designed, how we operate as a society, and how we treat the environment. Without awareness of these biases, we get stuck supporting unhealthy status-quo structures or chase after trends because people can only see things in a certain way.

While we all have a role in shifting our social paradigm towards healthier states of being, design professions have much more potential to support people in discovering different ways of seeing in the world than is currently realised. Through design of spaces, we can change the way we see. But first, these individual designers (including architects, landscape architects, engineers, planners etc.) need to the possibilities through their own eyes first.

Therefore, learning to broaden our field of vision to see the world in different ways can be beneficial for both personal and social well-being. This does not mean that every landscape design needs to become an existential lesson—although this can very much happen if we want it to—but a conscious awareness that we are always in relationship with other elements in the world should become common practice in design professions.

Landscapes have much wisdom to share with us, but we need to give them a chance by opening our eyes and ears to them.